Teen horror’s female protagonists are regularly drawn to boys they have been warned away from: alluring bad boys. Sometimes these guys have just moved to town and no one knows where they’ve come from or what their lives were like before, and this mystery breeds speculation and gossip. Sometimes they have bad tempers or a rumored history of violence. Sometimes they come from the “wrong side of the tracks” and offer few details of their lives at home because they feel ashamed of their family’s lack. In most cases, the female character discovers that her bad boy isn’t really all that bad, just intensely private, traumatized by some past horror, or he’s a misunderstood loner waiting for the right girl to come along and understand him (an unsettling and potentially dangerous message for teen readers to be soaking in, to be sure).

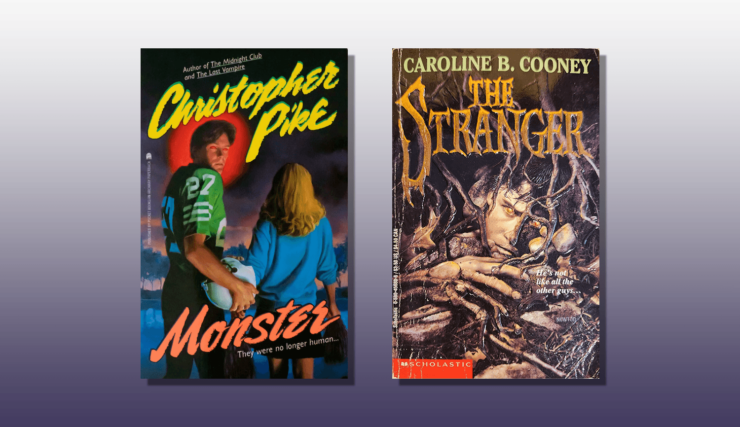

But every now and again, the bad boy is actually an inhuman monster capable of death and destruction, like in Christopher Pike’s Monster (1992) and Caroline B. Cooney’s The Stranger (1998).

Christopher Pike opens Monster with a scene of shocking violence, as Mary Carlson walks into a high school party with a shotgun and kills two of her classmates—Todd Green and Kathy Baker—without saying a word. Angela Warner is relatively new in town, but she and Mary became fast friends right from the start, spending all summer together, and when Mary starts shooting, Angela attempts to stop her. Mary remains intent on her purpose though, pursuing her boyfriend Jim Kline through the house and into the woods. Angela comes to Jim’s rescue and as she stands between Jim and Mary, Mary tells Angela that “I have to kill him … Because he’s not human” (16). Mary is apprehended and taken into police custody, her rationale dismissed as the ravings of an unhinged mind. Angela’s the only one who seems to be interested in what Mary has to say, though even she assumes that Mary is speaking metaphorically: she’s willing to believe that Todd, Kathy, and Jim may have done something inhuman, committed some atrocity that Mary might believe needs to be paid for with their deaths, but not that they are actually literal monsters.

Buy the Book

Gothikana

But that’s exactly what Mary is suggesting: that Todd, Kathy, and Jim have become something other than human, something physically and biologically monstrous. Todd and Jim are football players and Kathy a cheerleader, and Mary tells Angela about looking into the weight room one day after practice and seeing them lifting thousands of pounds, demonstrating inhuman strength and endurance. But that’s nothing compared to the night Mary followed the three of them to a bar and saw them leave with two other couples to go to an abandoned warehouse, with only her three classmates emerging from the encounter alive, the bodies of the other couples simply gone and trace amounts of blood left behind on the warehouse floor. While these are some disturbing observations, Mary is largely dismissed as hysterical: there’s no one else who can corroborate what she saw, she was basically stalking the teens she killed, and it turns out that Jim was her ex-boyfriend, having recently told her he wanted to see other people. As far as many of the characters are concerned, that’s case closed. Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned and when a teenage girl is dumped, she just might tell everyone you’re an inhuman, murderous monster and shoot your friends.

Angela is less willing to dismiss Mary’s story, though she’s also pretty excited about spending some intimate time alone with Jim. He may be turning to her for comfort and understanding in light of their shared near-death ordeal or he may be getting close to her to find out how much she knows. Either way, they end up at Point Lake near Angela’s house with Jim forcibly kissing Angela, trying to take off her clothes, and then bleeding all over her from a cut on his arm that he got while chasing her through the woods. Jim dismisses Angela’s concerns and keeps kissing her, “But they were so smeared with gook that the passion had lost all charm for Angela. Well, most of the charm” (85). She finds herself simultaneously drawn to and repulsed by Jim, thinking to herself that “It still felt good to have his mouth on hers. He tasted great” before realizing that “Angie, dear, that might be the taste of his blood” (85, emphasis original). This interaction basically sets the tone for Angela and Jim’s relationship moving forward: he pushes, she tells him no, he doesn’t listen to her, and she eventually decides it’s all okay. They share another few bloody and sexually-charged interactions, the most memorable of which involves licking one another’s blood while they’re naked and intertwined in the middle of Point Lake, and Angela finds herself craving Jim even as she carries out a parallel investigation that seems to corroborate Mary’s story and affirm Jim’s monstrosity. Jim’s difference becomes even more undeniable as Angela herself starts to change, having terrifying nightmares of a past life on an alien planet, finding herself craving blood, and suffering splitting headaches if she doesn’t consume it.

Angela maintains enough of a hold on her mind and identity to track down a local shaman and a geologist to find the pieces she needs to solve the mystery (there’s something in the water, extraterrestrial in nature, from the meteor that made the lake a hundred thousand years ago), identify the monsters (the football team and cheerleaders, because they drink the most water), and come up with a plan to destroy them (homemade bomb). She is even able to spend some time ruminating on the nature of these creatures’ monstrosity. As she reflects, “They craved human flesh but preferred to eat people alive—that made them ghouls or zombies. In a sense they were from outer space—that made them aliens. But they liked human blood—she liked human blood for god’s sake—and if the myths and her nightmares were true, they mutated into batlike beings” (176-177, emphasis original), with Angela ultimately choosing to define the creatures as vampires. There are some hiccups in her plan but in the end, she blows up the house with all of the monsters inside, though to anyone else it really just looks like a horrifying accident or potentially a mass murder that killed thirty-two teenagers. But that’s not fallout that Angela has to deal with, because she’s got bigger problems. It turns out that this isn’t a “kill the head monster and everything goes back to normal situation” and in the book’s epilogue, readers get one last glimpse of Angela, now transformed into a winged creature with red eyes and long talons, no memory of her life before, and the last vestiges of her humanity held in check by an amulet the shaman gave her. Watching from the trees, “The creature simply existed and fed while time passed” though thanks to the amulet, it remembers that “There was something wrong about killing humans … People were not for eating” (229). While this is all well and good—especially for the police officer the creature is watching from its tree—it definitely leaves the door open for more horrors to come. It’s likely only a matter of time before the creature’s biological imperative drives it to make more creatures and if the amulet is ever lost or broken, all bets are off.

While Angela is the new girl in Monster, in The Stranger it is a new boy who catches Nicoletta Storms’ eye. Nicoletta is a previously-privileged girl, whose parents have fallen on hard financial times. The family has had to move from a mansion in a gated community to a slightly run down ranch-style house, where Nicoletta has to share a bedroom with her younger sister Jamie. Her life is further upended when a new girl, Anne-Louise, moves to town, auditions for a spot in the highly competitive Madrigals choir, and takes Nicoletta’s place. Losing her spot in the choir would be bad enough, but her fellow Madrigal singers are also pretty much the only friends that Nicoletta has. She finds herself alone, on the outside looking in.

Things are looking pretty grim when Nicoletta shows up for Art Appreciation—the class she begrudgingly added to take the place of her former Madrigals’ rehearsal time—until she spots the mystery boy. Sitting in the dark as the teacher shows slides, Nicoletta watches as “Several times he lifted a hand to touch his cheek, and he touched it in a most peculiar fashion—as if he were exploring it. As if it belonged to somebody else, or as if he had not known, until this very second, that he even had a cheek” (10-11). Even when the lights come back up, “The boy remained strangely dark. It was as if he cast his own shadow in his own space” (11). He’s mysterious, he’s different … and he completely ignores her. So Nicoletta does the only logical thing: she blows off her friends and follows him into an isolated area off a dead end road, to a trail that leads into the woods. When he turns around to see who has been following him, Nicoletta hopes this will be the start of a grand romance, but instead, he just offers to walk her back to the main road while she tells him about her crappy day. Nicoletta pours her heart out to him but he remains a blank slate: “He simply nodded. His expression never changed. It was neither friendly nor hostile, neither sorry for her nor annoyed with her. He was just there” (20). He gets her back to the road, introduces himself (his name is Jethro), and says goodbye, though he does agree to have lunch with Nicoletta at school the next day.

Nicoletta finds herself obsessively thinking about Jethro, while at the same time being wooed by her former fellow Madrigal Christopher, a previously noncommittal ladies’ man of sorts who everyone calls Christo. Christo’s nice, and all of Nicoletta’s friends are jealous, but all Nicoletta really wants is to follow Jethro into the freezing cold woods again, plagued by the mystery of who he is and where he was going. So she heads back to the woods, follows the path he was blocking during their first encounter there, and finds a cave. Just within the entrance of the cave, the walls are beautiful and “seemed to emanate light … smooth and polished like marble” (46). But the cave soon becomes dark and dangerous, with a steep drop off and no way out. When Nicoletta screams for help, she is saved by “A creature from that other, lower, darker world … Its skin rasped against hers like saw grass. Its stink was unbearable. Its hair was dead leaves, crisping against each other and breaking off in her face. Warts of sand covered it, and the sand actually came off on her, as if the creature were half made out of the cave itself” (49). Nicoletta is filled with an uneasy mixture of revulsion and gratitude as the creature deposits her back to safety and tells her to “Never come back” (50).

This seems like pretty easy advice to follow, all things considered, but as Nicoletta connects the dots between Jethro, the cave, and the creature, she can’t stay away, returning to the cave again and again. Jethro is the creature of the cave, cursed to spend eternity as part of its walls. He can take human form and pretend to be a normal teenage boy when it’s sunny out, but on overcast days, he is unable to cast this glamor, trapped in his monstrous form. He has been there for hundreds of years: he and his family were early settlers in the area and when his father fell into the cave, Jethro offered to take his place, certain that his father would go get help and come back to rescue him. But the influence of the cave makes those who have seen it forget all about it and no one came to save Jethro. Others have fallen into the cave in the years since, similarly absorbed and trapped, becoming part of the cave and cursed with a dark immortality. Jethro’s story is tragic and Nicoletta sees him as a victim of circumstance … until two hunters go missing and fall into the cave, and he refuses to rescue them, telling Nicoletta that that’s just the way the cave works. She feels horrible for their families, tortured by the thought of them never knowing where their loved ones have gone, whether they’re dead or alive, or their final fate, but Jethro is unmoved.

Following this revelation, like Angela with Jim, Nicoletta finds herself simultaneously drawn to and horrified by Jethro. She can’t stop thinking about him and even plans to sacrifice herself to the cave in exchange for his freedom, but she also can’t come to terms with the fact that he is willing to let innocent people die when he could easily save them. He saved Nicoletta with no trouble at all–and while we could argue that he did that because he loves her and wants to protect her, he also saves Anne-Louise too when falls into the cave (and Anne-Louise immediately develops the same obsessive fascination with and desire to return to the cave in the aftermath) so it could just be that he likes girls. Jethro realizes that he has set an unstoppable and fatal series of events into motion, with two girls now obsessively pursuing him and Christo attempting to hunt “the monster” down, and takes matters into his own hands, blowing up the entrance to the cave, entombing himself and the cave’s other victims inside.

Jim and Jethro definitely raise the bad boy stakes in ‘90s teen horror. They might be complicated and misunderstood, but they’re also literally inhuman and have intentionally killed people, with little hesitation or regret. These two also remain on the periphery of the standard “girl meets monster” romance trope, because neither of them really fit neatly into any established monster category. In Monster, Angela thinks of Jim and the others as vampires, but as her thought process reveals, it’s really not as clear cut as all that. Both Jim and Jethro also have intimate connections to the land itself, with Jethro an inextricable part of the cave and Jim and the others fundamentally grounded in the meteor that brought this voracious alien life to Earth. They remain beyond the bounds of definition, monstrous individuals who are also only one small part of a much larger collective body. Even if Angela and Nicoletta could win them over with love and acceptance, Jim and Jethro cannot separate themselves from the body into which they have been absorbed: they may have individual consciousness, emotions, and desires, but their identities are subsumed by the collective.

These encounters with monstrosity are also oddly liberating for Angela and Nicoletta, though in a limited and damaging way. Both girls find themselves acting in ways they would not usually act, straying from the prescribed high school social script to follow their own desires. They actively pursue power and they claim knowledge that remains beyond the reach of their more conventional peers. As Angela begins to put the pieces together, she still finds herself drawn to Jim, reflecting that “there was a part of her that was in love with the dark side. There always had been, really—it was probably the same in all people” (130). Angela follows this attraction and ends up paying for this indulgence with her humanity. The stakes aren’t nearly as high for Nicolleta, who will likely be haunted by this lost love and her new understanding of the world, but she hasn’t been fundamentally, biologically changed or severed ties with humanity, as Angela has done. They have loved these bad boys, walked on the wild side, and paid a price.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.